In the rapidly evolving landscape where corporate productivity tools and legal risks collide, Desiree Sainthrope stands as a crucial guide. With deep expertise in global compliance and the legal implications of emerging technologies, she offers a clear-eyed perspective on the challenges organizations face. The widespread adoption of generative AI tools like Microsoft Copilot has introduced a new, complex data source that legal teams are just beginning to grapple with. This has created a host of tricky questions around e-discovery, data governance, and corporate liability that demand immediate attention.

This conversation explores the practical realities of managing this new frontier. We delve into the critical issues of handling AI interaction data in discovery, the unforeseen risks of employees sharing sensitive information with these tools, and the challenge of ensuring AI-powered searches are defensible and consistent. Furthermore, we examine the persistent problem of employees using unauthorized AI, a practice that creates significant security and legal vulnerabilities.

As Copilot interactions are automatically stored in user mailboxes, they are now appearing in e-discovery. With judges starting to ask for this data, what practical steps should legal teams take to prepare for discovery requests, and how should they advise clients on retention policies for this new data type?

This is a trend that began picking up steam last year and is now a central issue. Because most organizations operate within the Microsoft 365 ecosystem, these Copilot interactions are captured in user mailboxes by default. This means that during routine custodian collections, this AI-generated data is now being swept up alongside emails and other documents. While there haven’t been any landmark rulings that set a firm precedent, I have heard directly of cases where judges are actively saying, ‘No, we really want you to include this.’ The “wait-and-see” approach is becoming increasingly risky. Legal teams must advise clients to get ahead of this by classifying this data now, deciding on clear retention policies, and treating it as a standard part of their discovery playbook rather than a novel exception.

Employees might inadvertently feed sensitive data, like PII or confidential sales figures, into a generative AI tool. How does this create unforeseen e-discovery risks, and what specific governance or training protocols can organizations implement to mitigate the accidental exposure of this information during litigation?

This is a massive security concern that has a direct and dangerous line to e-discovery. An employee might innocuously ask an AI to analyze sales data, but the spreadsheet they upload contains sensitive, confidential information. That entire interaction—the prompt, the data, and the AI’s response—can become a stored record. When that record surfaces later in e-discovery, you have unwittingly exposed something that should have remained protected. The key to mitigation is proactive governance. Organizations need strict protocols that clearly define what data is permissible for use in AI. This must be paired with comprehensive employee training that goes beyond a simple memo. You have to show them real-world examples of how quickly a helpful query can turn into a critical data leak.

AI search tools can yield different results based on minor changes in query phrasing or unannounced updates to the underlying AI model. How can e-discovery teams ensure defensible, consistent results, and what validation steps should they perform before relying on an AI-powered search tool for critical matters?

This is a core challenge to the defensibility of using AI in e-discovery. Consistency is everything. You can have a situation where one person runs a search, and a second person runs what should be the equivalent search but uses slightly different language, and they get entirely different results. There’s also a more technical risk that many lawyers aren’t thinking about: the underlying models from providers like OpenAI or Microsoft are constantly being updated. A change to the model changes how the AI “thinks,” which in turn changes the results it produces. To ensure defensibility, you must keep a human in the loop. The AI can do the heavy lifting, but a person needs to direct it and, most critically, check up on its results. You have to implement a validation process to confirm the outputs are stable and reliable before you can confidently stand by them in a legal matter.

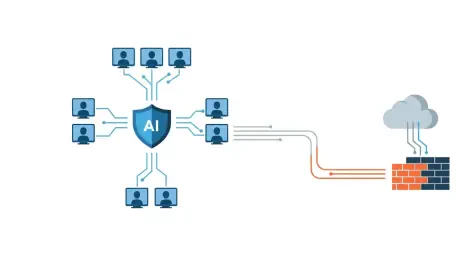

Many companies sanction a secure tool like Copilot, yet employees may still use unauthorized web-based AI for work. What technical or policy-based monitoring strategies are most effective for managing this risk without stifling productivity, and what are the legal implications of discovering unapproved AI use?

This is the classic “shadow IT” problem adapted for the AI era, and it’s a significant vulnerability. An organization may invest heavily in a secure, environment-bound tool like Copilot, but an employee might just prefer the interface of a public web-based tool like ChatGPT and use it for their work. When they do that, they are operating completely outside the company’s security and governance controls, creating a huge problem. The most effective strategies involve a combination of technical blocks and vigilant monitoring. A whole host of security solutions have emerged that can monitor for and block the use of unauthorized AI. Having that security in place is absolutely critical. From a legal perspective, discovering such use could trigger internal investigations and raises questions about data spoliation and the preservation of potentially relevant evidence that now exists outside the corporate environment.

What is your forecast for e-discovery, specifically regarding how courts and legal teams will classify and handle generative AI interaction data over the next two to three years?

I believe that within the next two to three years, treating generative AI interaction data as a standard and expected category of electronically stored information (ESI) will become the norm, not the exception. The “is this discoverable?” debate will largely be settled, and the focus will shift dramatically to the “how.” We will see the development of specific protocols and best practices for the collection, processing, and review of this unique data type. Courts will likely become less patient with arguments of novelty or undue burden, and legal teams will be expected to have the technical competence to handle these materials efficiently. The conversation will evolve from whether to produce this data to sophisticated arguments about the scope, context, and relevance of specific AI-driven conversations.